The welfare-hating justice takes lavish handouts

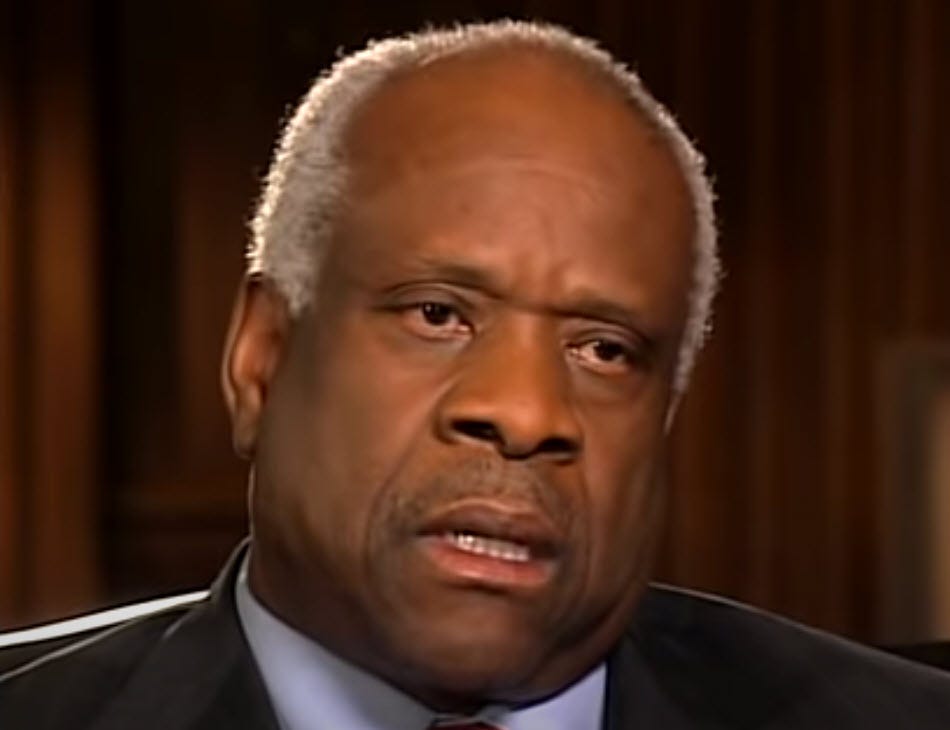

Clarence Thomas once humilitated his poor sister for getting handouts. But hers paled in comparison to his high-dollar gifts.

I’m tired of blacks being thought of only as poor people.

Those are the words of Clarence Thomas, a then-unknown lawyer who Juan Williams interviewed for a profile in the Washington Post. Williams discovered Thomas at a small conference of Black conservatives in 1980, when he was only 32 years old. At the time, Thomas’s biggest accomplishment was having graduated from Yale law school.

But Thomas had a clear message. He was intent on presenting an image of himself as having overcome poverty in his youth through sheer grit. He frowned on any assistance from the government for Black people. He even cruelly castigated his own sister.

“She gets mad when the mailman is late with her welfare check,” Thomas said. “That is how dependent she is.”

The irony 43 years later is now we know that Clarence Thomas has been taking handouts all of these years. In a blockbuster expose by ProPublica, we learned that Thomas accepted lavish gifts from wealthy individuals, gifts that likely totaled in the millions and included at least 38 destination vacations, 26 private jet rides, and a dozen VIP passes to sporting events.

That doesn’t include earlier revelations that Thomas’s mother lived rent-free and a young relative Thomas raised was getting his tuition paid, both courtesy of Texas real estate billionaire Harlan Crow. Nor does it include a mysterious private loan for a $267,000 luxury recreational vehicle that Thomas proudly showed off on 60 Minutes. Thomas refuses to say whether he ever repaid that loan.

Thomas is a paradox of a man. He is an ardent opponent of affirmation action although he may be one of its biggest beneficiaries. And he opposes the welfare system while reaping the benefits of influence peddling.

Thomas grew up dirt poor in Pinpoint, Georgia, where his shack of a home didn’t even have indoor toilets and Thomas didn’t even speak English. Instead, he spoke a local dialect handed down by slaves who settled in the area.

But during middle school, through sheer luck of the draw, Thomas’s life changed dramatically. He moved in with his middle-class grandfather and began attending a private Catholic school. His mother and sister were left behind to continue to struggle in poverty. Thomas never seemed to acknowledge the effects of the advantage he got.

Affirmative action unquestionably helped Thomas get into the College of Holy Cross and later Yale law school, which had just established quotas to admit black students. The feeling that others didn’t think he earned his way infuriated Thomas.

“You had to prove yourself every day because the presumption was that you were dumb and didn’t deserve to be there on merit,” Thomas told Williams.

Every time you walked into a law class at Yale, it was like having a monkey jump down on your back from the Gothic arches… The professors and the students resented your very presence. - Clarence Thomas, The Washington Post, 12/16/1980.

Thomas was liberal as a student but learned later that being a conservative well-educated Black man made him a rare commodity. He told Williams:

I marched. I protested. I asked the government to help Black people. I did all those things. But it hasn’t worked. It isn’t working. And someone needs to say that.

After law school, Thomas was angry because no major law firm, or really any law firm, offered him a job. Instead, he somehow ended up working for Sen. John Danforth in Missouri, making $10,700 a year, according to the book Strange Justice: The Selling of Clarence Thomas, by Jane Mayer and Jill Abramson. That’s where he was when he met Williams.

Sadly, he was wrong about his sister. She wasn’t actually on welfare at the time. According to Mayer and Abramson, she was working a double shift making a minimum wage of $2.35 an hour. She resented the fact that he didn’t give her credit for taking care of a sick aunt when she was receiving welfare.

The shortage of Black conservatives led to job opportunities during the Reagan administration, first in the civil rights office of the Department of Education and later as the head of the Equal Opportunity and Employment Commission. But despite not having any judicial experience, Thomas began carefully positioning himself to become a Supreme Court justice, first landing a seat on the U. S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

When civil rights icon Justice Thurgood Marshall finally retired in 1991, Thomas was one of the few conservative Black judges on President George H.W. Bush’s list to fill the seat. When Marshall realized he might be replaced by Thomas, he was sickened. In a press conference, Marshall said appointing a Black justice to replace him should not be used as an excuse.

An excuse for what, a reporter asked.

“Doing wrong,” he replied. “I mean for picking the wrong Negro and saying, ‘I’m picking him because he’s a Negro.’”

Marshall considered Thomas a sellout who rejected for others all the programs from which he had benefited.

Marshall had no way of knowing that the man who pretended to make it all on his own would go on to take millions of dollars in gifts from people who potentially had an interest in how he would decide cases. Thomas, for his part, decided not to reveal his gifts, flouting financial disclosure rules.

In the end, the man who claims he overcame poverty on his own was living a surreal life of wealth by choosing to forgo ethics.

At least Thomas didn’t have to wait by the mailbox for his checks.